This article was written by Leigh Allen, PWLTMN

Being retired I am outdoors more often, and around people much less often, than in previous years. I look inward and read more books. Sometimes I wonder if I’m losing touch with a part of the world that used to make up much of my life, mainly my conversations with other people. Am I losing out on the wisdom gained by interacting with not only family and friends but also with the random people that I would meet during my day?

As I ponder that thought, I turn to books again. Since I spend so much time in nature I turn mostly to modern nature writers. I am struck by the connections and language that writers like Robert MacFarlane and Helen McDonald effectively use in describing the natural world around them. They look deeply at the world around them and come away with a sense of how connected nature and the world populated by humans are. Younger writers like Dara McAnulty (Diary of a Young Naturalist) are following in their footsteps with writings rife with beautiful language and the connections between nature and life. Through their writing runs a consistent thread of reverence for life and the natural world. A reverence for all parts of it, the good, the bad, the violent, the beautiful, the ugly, and the necessary. They each in their way impart a spiritual look on life by looking at nature.

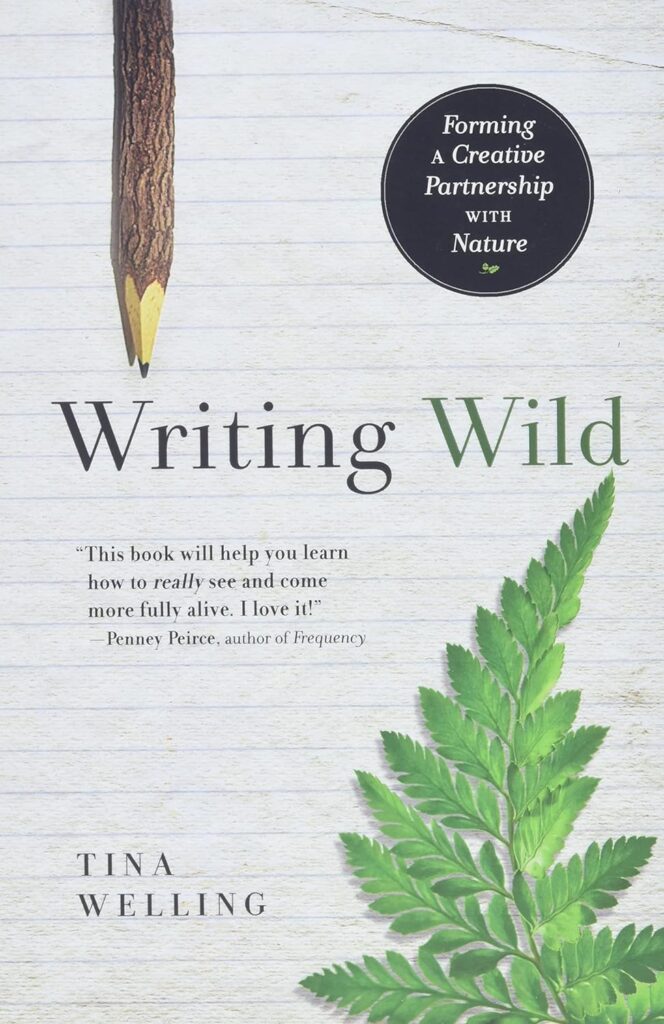

I want to make the same kinds of connections. It’s not enough to sit and observe life. I want to think about it and come up with my own words and connections. I found what I needed in a book called Writing Wild by Tina Welling. In it Welling lays out a system of observing nature and writing about it effectively. She takes it further, though, and includes step-by-step instructions to make connections between what you observe and your own thoughts and memories.

Welling calls her system a Spirit Walk and the major steps to a Spirit Walk are naming, detailing, and interacting. This sounds simple enough, but Welling wants you to use all five of your senses when you are out in nature. It becomes apparent in the early part of the book that this is going to be a more detailed system than it sounds.

In the naming task, you take the time to sit and jot down all that you see around you. That’s it. But you name everything you see and hear and feel and smell and taste. Taste? How often do you think about using taste when you are on a walking trail? This task is a quick one and one-word lists are fine. By using all five senses for this activity you train yourself to become more observant of everything around you. Most times we hone in on a few significant things in our immediate environment. The simple act of giving everything a name helps it become more important to us.

For the second task, detailing, you choose one item and sit with it. You think about how it makes you feel. What are your reactions to it? If you’re like me you look for new or unfamiliar words to describe things you don’t normally think about. The spikes on a Sweetgum ball are spiny lobes that look like some sort of scaled-down medieval torture device. That’s not the way I would normally describe something I looked at. Then you ask “How does it make me feel?” At this point, you are moving past being an observer and becoming more of a participant. You are connecting the item to yourself by realizing how it affects you.

The third task is where you make connections and where walking plays a large part. You walk for as long as you need with the awareness of your surroundings and how you feel until you remember events or emotions connected to something in your life. As she says, these are your stories. This is what you need to write down. You are making connections even if they seem insignificant. If there are questions in your life at the moment, how are your thoughts connected to them?

A large portion of Welling’s writing is devoted to bringing things in our world into our consciousness, whether it’s things we see but don’t usually observe in detail, or thoughts that we dismiss because we don’t think they’re important. You make your thoughts physical by writing them down. There are chapters on becoming aware of our body, that are much like processes we go through during meditations. She shows how to ask questions and find answers by writing about what you “want” to know. When you are more open to what is going on around you, answers to your questions come more quickly. She touches on creativity and how to get past being blocked. As she states in the book “two strands prevail. One strand is an awareness of fully inhabiting place. The second strand of experience is the awareness of self. You braid the two strands together with a third, your writing.” Writing it down is the key to understanding the connections.

She also writes about the writing process itself and how writing isn’t balanced if it’s only about external experiences or internal experiences. It has to be a mixture of both. This is what good nature writers do, and why I enjoy their writing so much. There are plenty of writing exercises sprinkled throughout the book in addition to going through the exercises for trying your own Spirit Walks.

While some may have less interaction with nature but more interaction with humans, we can still learn how to connect the physical world with our inner world. Writing Wild provides a system to do just that. I found myself marking many passages as “key”. It is an enjoyable read and a book I plan to use over and over again, even (and maybe especially) if I return to interacting more with people.