Haiku and Prose by Randy Bissell

A few years ago, I read a series of magazine articles about how wild horses, often called mustangs, were being destroyed and removed from public and private lands in the Western United States because they had become a nuisance. The piece went on to explain that horses were not indigenous but considered an introduced species that competed with the scarce grass needed for cattle. There were no horses in North America when Columbus arrived in 1492.

As a geologist, I recalled from my college courses that the horse evolved in North America. From the Eocene Epoch, some 40 million years ago to just before the end of the Pleistocene, about 12,000 years ago, horses were abundant in North America. Horses are uniquely an evolved species on our continent and coexisted with the other “megafauna” or big mammals of the Pleistocene.

Nature made me here.

Man forced me into service.

Never to return?

My own pursuit of the story and the voluminous work of others come together as tale about climate, geology, man, and horses. It seems the famous land bridge between Asia and Alaska first formed up about 4 million years ago and episodically thereafter. It allowed horses to migrate into the Old World in the Pliocene. Horses then populated southern Asia, Europe, and Africa.

The latest Ice Age is called the Wisconsin and it lasted from 120,000-12,000 years ago. That is when man came across to North America. Anthropologists are finding evidence that man arrived in the Pacific Northwest as early as 30,000 years ago. When man showed up in North America, he encountered many Pleistocene megafauna, including mammoths, mastodons, and horses. Evidence further suggests that he found them a great food source. Since reproduction rates on the largest animals tend to be the lowest and thousands of years is a long time for an open season on megafauna, it’s no surprise that extinction of most species was the result.

A story untold –

The man and horse migration.

Crossing destinies.

Evidence also suggests that horses were first domesticated in western Asia, perhaps Kazakhstan. The people there saw utility in this strong, beautiful newcomer to the continent. Some enterprising or courageous cowboy must have said “I believe I can ride that thing!” And he did. With domestication, the horse’s importance to the civilizations of Mongolia, China, India, Greece, Egypt, Rome, Spain, England, and many other cultures grew. The horse became an essential part of agriculture, ranching, and military conquest in Europe, Asia, and Africa. Horses were even used extensively in the European theatre of World War II.

Meanwhile, back in North America, horses became extinct after about 12,000 years ago. Was it caused by man? Or did they disappear due to disease or climate change? Asteroid impact in Greenland? Whatever completely sealed the horse’s fate is unknown. But prior to their re-arrival with the Spanish explorers in the 1500s, the horse was absent from North America and a mystery to the cultures of the native peoples of the Americas before Columbus.

The Spanish, Portuguese, and French loved their fine horses and brought them across the Atlantic to aid in exploration and colonialization. The Mesoamerican natives had never seen a horse, nor had they experienced the fury of mounted Spanish soldiers. Great Aztec armies fell before the Cortez. From the 1500s into the 1700s horses were released, escaped, or were abandoned to the wilds of North America. The majestic and rugged landscape was not foreign to them, remembering they evolved here. Horses were perfectly adapted to the expansive grasslands and scrublands of the “New World.” They thrived.

Having seen the power of the horse demonstrated by the conquistadors – or perhaps simply realizing their practical utility, some enterprising or courageous native American must have said “I believe I can ride that thing!” And he did. By the time the young United States was fulfilling its manifest destiny in the early 19th Century, the “American Indian” had 200 years to develop skilled horsemanship. In the mid-1800s, the horse was ubiquitous across the American West, as a pack animal, form of transportation, instrument of war, and wildlife.

Wild horse, oh, mustang

In name, still here – around us!

Desert to island.

The presence of the horse in South Texas is evidenced in the place names familiar to us. Mustang Island was so named for the Spanish horses there. Likewise, we have the Wild Horse Desert of South Texas and Northern Mexico. With ranching and settlement, the wild horse became a rare site in Texas, succumbing to displacement, domestication, and extermination. The last of the mustangs on Mustang Island disappeared in the late 1800s, as the island became dotted with townsites and cattle were introduced.

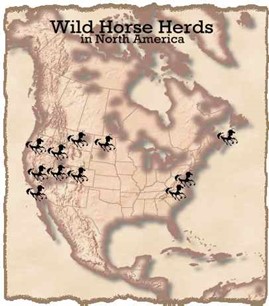

In America today, horses run free and they are protected in many places. Mustangs are found on Atlantic coastal islands in Virginia and Georgia. Wild horses occur in Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and even in Hawaii. The US Bureau of Land Management stewards horses on public land. Where horses are over-populated or deemed a nuisance, they are more humanely relocated, domesticated, or sometimes destroyed. Horse hunts can thin herds and limit populations.

The future unclear

Regarded as a nuisance.

In a land once theirs.

Legislation has protected many wild horses in the American West, but it is still debated about how to regard their presence. Is this horse, a legitimate Pleistocene megafauna, a foreigner in North America? Or are they home? Our cultural fondness for the horse, nostalgia, and raw emotions cloud the debate on management practices and protections for mustangs.

My, they are beautiful! It is delightful consider the days they ran free in Texas – just 150 years ago. And then, before any written history, some 30,000 years ago when man was the “invasive species” in North America.

See the mustang here.

Galloping hoofbeats near?

Just a dream, I fear.