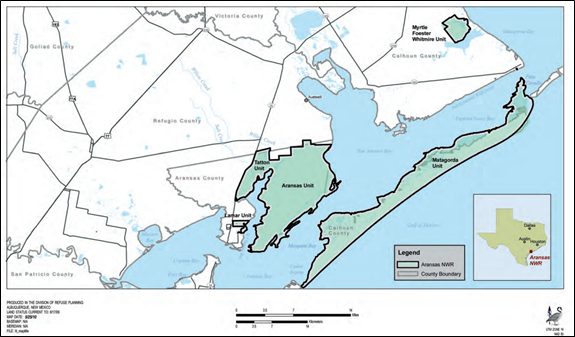

The Aransas National Wildlife Refuge operated by the US Fish and Wildlife Service is in parts of Aransas, Refugio, Victoria, and Calhoun Counties along the Texas Gulf Coast, about 2 hrs. north of Corpus Christi. There are five subdivisions or Units of the Refuge. Most accessible and familiar is the Aransas Unit made famous as the winter home of the whooping cranes, an endearing part of American conservation since the 1940s when the area was set aside by President Roosevelt.

Map showing the Units of the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge on the Texas Coast.

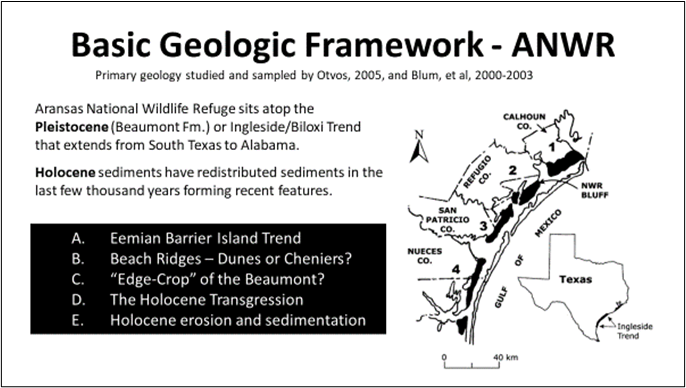

There are five basic geologic components of the landscape found within the Aransas Unit.

- The Beaumont Formation “Eemian” Barrier Island Trend. The greatest part of the Aransas Unit is made up of the ancient barrier island, part of a system of Pleistocene-aged islands extending from South Texas through Mississippi. These sandy deposits are about 125,000 years old and represent the formation of a series of islands in the late Pleistocene, not unlike the chain of barrier islands on the Texas Gulf Coast today. Sea level in this period was 5-7 m higher than today and the modern landform sits at that same elevation. Because of the sandy nature of the deposit, the Barrier Island is an important near-surface freshwater aquifer contributing continually to the estuarine environment.

- Beach Ridges, Dunes & Cheniers. Distinctive beach ridges or ridges and swales occur on the Eemian Sand Trend. These alternating brushland forests and fresh/brackish wetlands underpin a wide variety of habitats within the Refuge. The preservation of these distinctive ridges suggests rapid deposition and advancement (progradation) of the shoreline at the end of the Eemian high-stand period of sea-level 125,000 years ago.

Basic geological framework and map of the Pleistocene Ingleside Barrier Trend.

- The “Edge-crop” or Wisconsin Ice Age erosional edge of the Beaumont Formation. When sea level began falling during the last Ice Age, the landscape was left as uplands, subject to erosion over 100,000 years. Sea level fell to over 100 m lower than today. Time and elements sculpted the new uplands as rivers like the Nueces, San Antonio, and Brazos carved deep river valleys across the newly exposed continental shelf. The edge of San Antonio Bay and the contact of the Pleistocene sediments with the Holocene bay fill represent the edge of the preserved Beaumont sands and shales.

- The Holocene Transgression. Sea level began to rise about 11,000 years ago and we call the time since the Ice Age, the Holocene, or modern epoch. The rise of sea level has inundated the ancient river valleys forming modern estuaries such as San Antonio Bay, Copano Bay, Corpus Christi Bay, Galveston Bay, Mobile Bay, and the Chesapeake Bay. These modern inland bays are the expression of the sea rising into the river valley and that process continues to this day. The process has slowed in the last few thousand years, allowing the bays to fill with sediments and the chain of modern barrier islands, like Padre, Mustang, St. Joseph, and Matagorda to form. The shallow waters of San Antonio Bay are filled with the sands, silts, and muds of the Holocene Transgression.

- Holocene erosion and sedimentation. Sediment erosion and transport continue as a process to this day and it is impacting some of the most visible “Public Use” areas of the Refuge, namely Mustang Lake, Dagger Point, the picnic area, and Heron Flats. Several factors seem to be affecting the stability of the sea cliff along the most visited part of the park, the roadway from the visitor’s entrance to the observation tower platform. Erosion is likely due to recent sea-level rise and the energy from the wakes of boat traffic in San Antonio Bay and the Intracoastal Waterway along Mustang Lake.

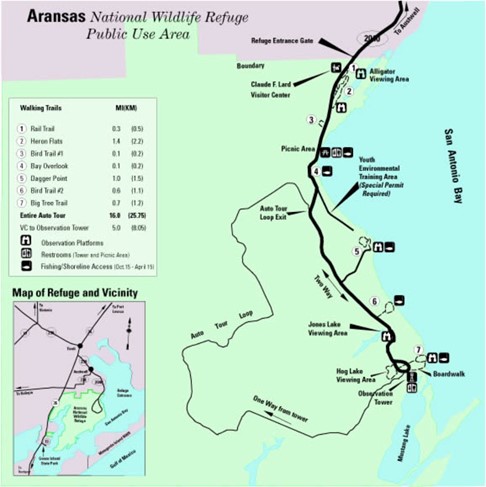

Visitors Map of the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge.

Summertime winds from the south may be eroding and moving sediments from Mustang Lake and the sea cliffs towards Heron Flats while winter winds from the north push sediments southward. The continual erosion, with back and forth migration of sediments coupled with the slow rise of sea level and increased boat traffic wave energy may be dispersing sediment into the bay rather than accumulating it at either site, Heron Flats or Mustang Lake. The resilience of these areas seems questionable and efforts are being made to stabilize the Mustang Lake area and protect it because of the important habitat for the whooping cranes.

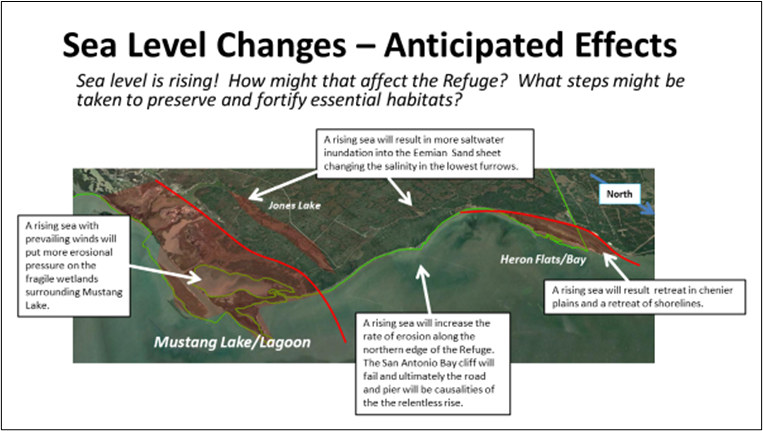

Anticipated changes in sea level may challenge habitat preservation efforts in the Refuge due to the nature, type, and distribution of landforms. A rising sea will result in more saltwater inundation into the Eemian Sand sheet that makes up the greater part of the Refuge. Salty bay water is denser than fresh water and it will tend to underride and infuse the shallow meteoric freshwater within the highly permeable sand sheet. This may affect the salinity or brackishness of the water features in furrows between ridges, such as Jones Lake, the lowest areas on the sand sheet. As discussed above, a rising sea will put more erosional pressure on the fragile wetlands surrounding Mustang Lake. The rising sea will increase the rates of erosion along San Antonio Bay due to bay cliff undercutting. Finally, a rising sea may reverse the accumulation of Heron Flats leading to rapid erosion.

How might sea level change impact the Refuge? Things to consider.

Aransas National Wildlife Refuge is a special place for Texas Master Naturalists to visit and explore. The geologic history and the modern biological habitat are inseparable in their essential ecological relationship. However, instability in the short-cycle geologic and climatic fundamentals jeopardize fragile ecosystems. A geological understanding of the landforms, causations, timing, and other predictable elemental responses in the coastal sedimentary system is essential to foresee, measure, steward, and positively address challenges in ANWR’s mission to preserve habitat and protect wildlife.

Randy Bissell

November 25, 2020