The sandy area of Corpus Christi’s downtown referred to as “North Beach,” the modern home of the Texas State Aquarium and the USS Lexington Museum has a rich and colorful history as part of the landscape and seascape of downtown Corpus Christi throughout the city’s 170 year history.

Gazing upon the bay’s largest beach on the other side of a shallow bayou back in the 1840s, you’d have seen a wide barren sand bar extending northeastward of the small Kinney’s Trading Post, the future Corpus Christi townsite. That sand spit tapered out against a shallow oyster reef that connected the two sides of the large bay and distinguished the Corpus Christi Bay from the Nueces Bay to the west.

Oysters were abundant in the shallow bays back then, and the water was likely much clearer because of the filtration they provided. Fish, fowl, and game were abundant in this paradise. It made the area a natural draw for native populations dating back thousands of years before the Europeans came and claimed this land.

President Ulysses S. Grant, a young Army officer and his soldiers wintered in Corpus Christi in 1845-46 with General Zachary Taylor, in preparation for the Mexican-American War that would finally settle the boundaries of Texas and complete the Manifest Destiny of a young nation reaching from the Atlantic to the Pacific across the continent.

Although the Port has isolated it today, North Beach is not naturally an island. It is, geologically speaking, a longshore-sediment-sourced “sand spit” that was once connected to downtown. Prevailing winds from the southeast have pushed sand from the bay to be deposited along the old shallow reef. A shoal ran northward towards modern Portland about where the causeway is today. In Nueces Bay, the wild Nueces River advanced and retreated into its own body of water, supplying freshwater and sediment to the back side of the oyster reef and spit that separated Corpus Christi Bay from Nueces Bay. As they are today, the Nueces Delta, Nueces Bay, and Corpus Christi Bay were three distinct ecological areas. With close study, remnants of their uniqueness can still be seen.

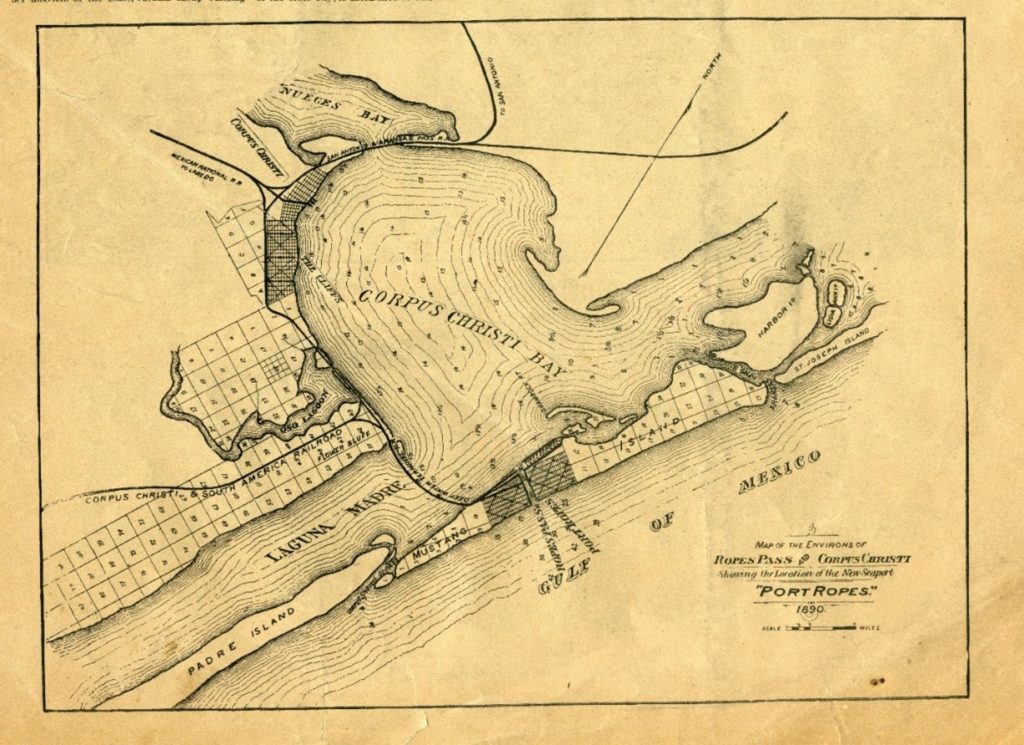

The extended downtown shoreline and “North Beach” that we see today have formed in the last 140 years or so due to the construction of the roadways, railways, and causeways that have increasingly connected Corpus Christi and Portland in the last century. It is said that a man could walk across the Bay on the shallow oyster reef that nature provided to connect the two sides – legendarily built up by natives with oyster shells. Wading and walking gave way to wagons on wooden causeways, then a train trestle as shown on the 1890 map above. Today there is a highway. With every new connection came more reinforcement of the landmass making a more substantial trap for the sediments naturally accumulating. Added to that natural accumulative process was the dredging of the Port and ship channels across the Bay. Is easy to see how that simple sand spit has evolved into the large sandy landmass developed for recreation and habitation in the early 20th and through to the 21st centuries.

The North Beach we see today shows the evidence of its cycles of development, change, and sometimes neglect. When the Bascule Bridge across the port existed through the 1950s, cars drove through a bustling North Beach, not over it like today. Tourist businesses and attractions thrived. Much of the pre-Harbor Bridge development has been lost – abandoned and cleared. With the high 1960s Harbor Bridge and elevated roadway, North Beach struggled to attract tourists and compete with popular Padre Island development. That changed in the 1990s with the construction of the Texas State Aquarium and USS Lexington. Developments of canal-front housing were built on the Nueces Bay side of the highway and causeway. Hotels and restaurants have recently been established and survived. There are people living on North Beach in cottages, condominiums, and RV parks. Things seem ready for a development on the ever-more-popular North Beach.

Over the years, man and nature have constructed, maintained, and modified a new sandy shoreline against the reinforcements of the robust bridge and causeway system. Birds inhabit the new wetlands and roost on the spoil islands. Nature finds a way. People enjoy the beach and tourist sites. The present-day landmass still suffers from a host of issues related to how elements of nature and influence of man converge and intertwine at that location. Tides, rain, wind, and poorly designed drainage conspire to regularly flood North Beach streets and lots. Bulkheads, riprap, groins, seawalls, retaining walls, causeways and concrete “protect” and reinforce some parts of North Beach – but other areas are left to erosion, decay, and subsidence.

Now in 2020, there are substantial proposals to build up the elevation of the land, provide resilient engineering solutions, improve access, and construct canals for better drainage and recreation. Higher and stronger retaining walls will be built to protect the landscape and infrastructure from storms. Through sound geoengineering, it appears that North Beach can be stabilized and protected as an asset to the city.

North Beach has come a long way from the spit north of Kinney’s Trading Post, and the sandy campsite of Ulysses S. Grant. A view from the air, it is an area with multiple uses and many challenges to maintain a balance between protection, utility, beauty, and function.

Randy Bissell, Texas Master Naturalist

Special Thanks to Carrie Robertson Meyer and Jim Moloney for contributions to this essay.