Our coastal State Parks, like Mustang Island State Park and Goose Island State Park, are great places to talk about and reflect on Spanish Exploration in the New World. Periodically, park interpreters and volunteers will present programs on Gold, God, and Glory, the motivations for Spanish Exploration of the Texas Coast.

In these coastal locales, there is offered a presentation on Spain’s obsession with gold in the New World following Columbus’s report to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella after his first voyage in 1492. By the early 1500s, Spanish ships were plying the Gulf of Mexico waters seeking adventure, treasure, religious converts, and bounty from the unfamiliar territories of Texas and Mexico.

The lands of Texas would yield no gold for explorers, few converts for Christianity, and little bounty. In the 70 years that followed Columbus, the Texas Coast, with its violent storms, inhospitable lands, fierce natives, and strong winds would deliver misery and death to many Spaniards. Likewise, the diseases brought from Europe would devastate the population of the New World.

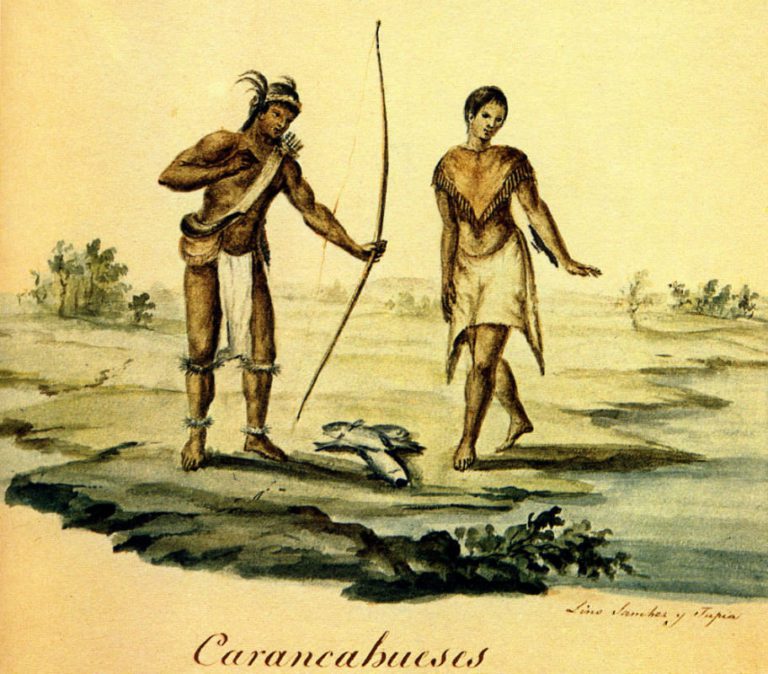

There was little to compare between the emerging Renaissance people of the 1500s Europe and the enduring culture of the native peoples of South Texas and Northern Mexico. The coastal people were known as the Karankawa – not really a “tribe,” a structure often ascribed to native Americans, but rather a language, family, and location-defined group of related peoples. A complex interweb of cultures, tongues, religions, and practices sharing a region and its resources. Mixing through intermarriage and conquest.

Spain’s obsession with gold and riches was foreign to the native people. Moreover, the Roman Catholic religion was difficult to understand. But the Spanish Sovereign’s claim to the New World and forcible conversion to Christianity were brought at the tip of a lance and the shot of a matchlock pistol or musket from the most armored and skilled horse soldier in the world, the Spanish Conquistador.

Alonso Alvarez de Pineda was the Spanish mapper and explorer who named Corpus Christi Bay in 1519. Not knowing the width of the North American continent, there was thought an easy passage to the Pacific. Mapping the coast of Texas, Pineda found only shallow, inland bays and small rivers behind the extensive barrier island system. Seeing the large bay behind Mustang Island for the first time on the Day of the Feast of Corpus Christi (Latin for the Body of Christ), he named the bay in 1519. More on de Pineda can be found at this website: https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/alvarez-de-pineda-alonso

Cabeza de Vaca Ivar Nunez was a Spaniard shipwrecked on Galveston Island in 1528 and spent eight years living amongst the coastal Karankawa and inland people towards the Rio Grande Valley. More about his story can be found on the website or through a simple Google Search. There is a Mexican movie on YouTube about his time in Texas and Mexico – however, be prepared for many inaccuracies in the portrayal of the land and the people. More on Cabaza de Vaca can be found at this website: https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/cabeza-de-vaca-lvar-nunez

The lost “300” of 1554. Three of four treasure-laden ships bound for Havana from Veracruz, Mexico were lost on the shores of Padre Island in 1554. Two-thirds of the 300 castaways may have died in the surf. A larger group of survivors thought it was a short journey back to Mexico. They ran afoul of the local Indians, and the trek turned into a death march with only one survivor. Later in the year, one of the three ships was still visible above the waves, Some of the wealth was recovered through salvage in 1554. Artifacts were found as recently as 1968 and can be seen at the Museum of Science and History in Corpus Christi. Read about it here: https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/padre-island-spanish-shipwrecks-of-1554