Gateway to the Brush Country – The Landscape of Lake Corpus Christi State Park

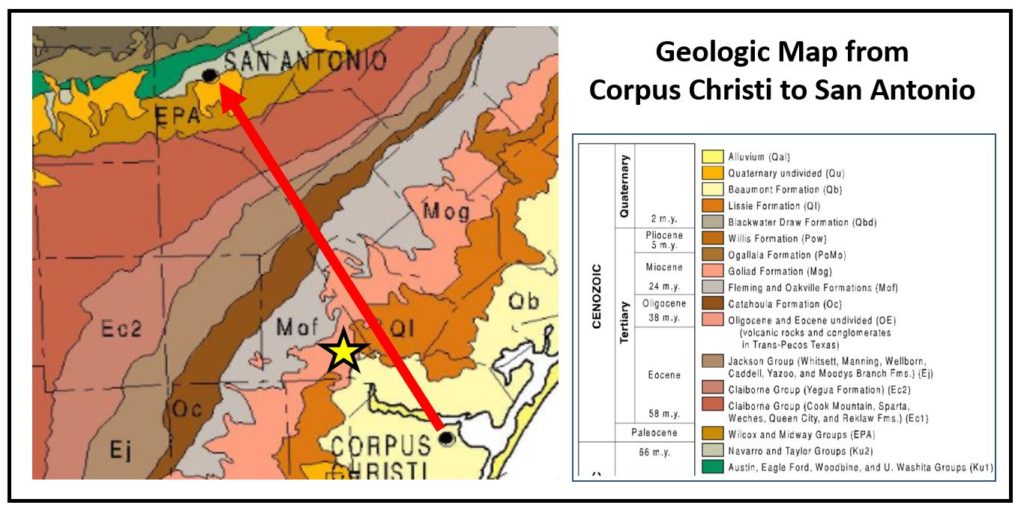

A drive to San Antonio is a 75-mph journey back in time. Starting at the present-day Holocene along our modern coast, we haphazardly careen through the entire Cenozoic Era. We travel back in time through the named Epochs and arrive 67 million years earlier in the Cretaceous Period limestones in San Antonio.

In Mathis, Texas, and up towards Swinney Switch, we drive over the riverbeds and coastal strata of the Miocene Epoch, some 4 or 5 million years ago. The “Goliad Sandstone” is the major geologic unit of that area and it is the prominent capstone of the numerous small hills and lovely ridges along the Nueces River Valley. More specifically, the named Goliad Formation is a late Miocene (or Miocene-Pliocene) aged sand-prone layer defining the boundary of the Gulf Coastal Prairie and the Brush Country ecoregions. The Goliad Sandstone is exposed as cliffs along the edge of Lake Corpus Christi, where the Nueces River has cut a deep valley in the past several hundred thousand years. The now-submerged floor of that valley is deep below the present surface of the lake. Lake Mathis, or now called Lake Corpus Christi, beautifully laps against the steep rocky cliffs of the Goliad sandstone.

The Goliad Sandstone is exposed as cliffs along the edge of Lake Corpus Christi, where the Nueces River has cut a deep valley in the past several hundred thousand years.

– Randy Bissell, Geologist

Most distinctively, the Goliad Sandstone is “caliche-fied.” Caliche is a common term used to describe the occurrence of calcium carbonate in soil and outcroppings of porous sands in arid climates. Calcite and other carbonate types of cement accumulate in the near-surface where mineral-rich waters get evaporated and evapo-transpired (imagine moisture-wicking) leaving behind voluminous carbonate mineral concentrations. In the Goliad Formation, these calcite concentrations can completely rearrange the sand grains destroying the original depositional forms and altering the rock to more like limestone than a sandstone both chemically and texturally. These calichefied sands are indurated (rock-like) enough to mine as building stones. The Goliad was also mined for building material to be crushed, mixed with portland cement, heated, and cast to make “calichecrete” bricks. The latter process required less skill and selectivity of rocks suitable for stonecutting.

But unlike brick and concrete which harden with time, calichefied sandstone and calichecrete are both soft, permeable, water-soluble, and thus subject to abrasion, softening, and erosion (and graffiti). The caliche-rich parts of the Goliad Formation are variable in the intensity of mineralization. It is not a uniform rock unit. Parts of the outcrops are very hard, dense limestone. Other places can be softer and chalky.

More importantly, there is more intense mineralization in the upper Goliad layers than those below. At the base of the outcrop, closer to the lake, the sand textures are not obliterated and remain readily recognizable. So, from top to bottom, the top is intensely calcified, while the bottom is less so. That makes for an “overhang” of large indurated blocks that often collapse along the edge of the lake due to the undercutting of softer strata near the shoreline.

The texture of the uppermost exposures of calichefied sandstone can be dangerous for walking and biking. In places, the texture of the hardest rocks is very rough – almost sugar-like (sucrosic texture) with sand grains embedded in crystalline calcite. This “tear-pants” sandpaper texture is unforgiving to skin and clothing (and tire sidewalls). A slip or fall on this material is treacherous, if not dangerous. The bottom line is that the Goliad Formation sandstone is variable horizontally and vertically – and those variations might make blazing, constructing, and maintaining a trail quite a challenge. Hike these hills with caution.

When visiting Lake Corpus Christi, try to consider the following:

- Why was this location selected for the construction of the Wesley Seale dam? How might the change of topography (elevation) have influenced the decision on the location and span of the dam?

- The first dam constructed on the Nueces River was earthen and locally sourced from the valley and Lissie Formation. It ultimately failed. Why might some soils be unsuitable for dam construction? Would sand be better than clay?

- When in the park, go to the old 1930’s Main Office overlooking the lake. It is constructed of both cut caliche stone and calichecrete, a mixture of crushed stone and portland cement. Do you see any differences in weathering? What weathers easier?

- There are three major soil orders in the park and a few others: Alfisols are well-developed soils with woodlands and thickets. Likewise, Mollisols are stratified soils supporting grasslands. Like mollisols, clayey soils produce Vertisols, identified by deep cracks when dry. In places, there are thin-to-no soils where plants have a tough time getting a foothold. These are called Entisols. Could you identify all of these? Try?

- What does the presence of a river in the Miocene in rocks overlooking the modern Nueces River say about geologic controls on the Nueces River? Why would a river reoccupy the same basic trend over millions of years of time? What bigger elements might control the route of a river?

Randy Bissell, Texas Master Naturalist & Professional Geoscientist