The Landscape of Barrier Islands: Padre Island and Mustang Island

Our barrier islands, where the land meets the sea is a beautiful, dynamic, serene setting on most days. South Texas Chapter master naturalists are blessed to have two primary beach sites to volunteer, educate, and contribute. These two gems are Mustang Island State Park and Padre Island National Seashore.

Padre Island and Mustang Island are part of the longest barrier island in the world, stretching 115 miles from the tip of Texas to Port Aransas. The system of Gulf of Mexico barrier islands extend intermittently around the entirety of the U. S. Gulf coastline. Barrier islands also occur along the Eastern Seaboard from Florida to New England. Worldwide, barrier islands and related sand spits are commonplace on the trailing edges of our moving continents where sand grains are easily accumulated by wave, wind, and tide on these “passive margins.”

Padre Island and Mustang Island are geologically young. These barrier islands have formed in the last 5000 years or so as sea level rise has slowed in the now warm Holocene modern geological epoch. About 18,000 years ago in the Wisconsinian Ice Age, the coastline of the Gulf would have been over 60 miles eastward of today’s with sea level 300 ft. lower. The stability of sea level in these past very few millennia have allowed our barrier islands to establish their present position and geometry along the Texas Coast. Interestingly, generations of the earliest South Texas natives saw the sea rise.

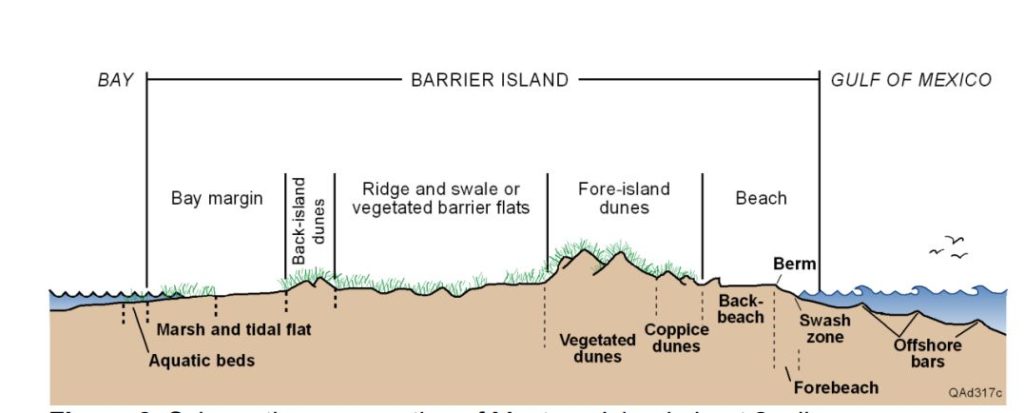

Looking across the island profile from west to east, or from Laguna to Gulf, we see a thin wedge or lens of sand. From the east comes the energy of wind and wave, sculpting the island. To the west, in the salty lagoon and bay, the shallow water teems with fish and fowl.

The island is miles across but only 30-50 ft. high. (BEG Texas)

The beach is just one part of the barrier island that is made up of the backbeach, the berm, the forebeach and the swash zone. Mustang Island and Padre Island do not mechanically sweep their beaches for litter, so these natural parts of the island profile are left intact. Behind the beach is the dune field, made up of small coppice dunes and large established vegetated dunes. Some dunes reach 30 or more feet above the beach and are comprised of thin beds of wind-blown sand. The oft-forgotten back side of the barrier island makes up most of the area and includes the ancient ridge and swale terrain associated with older “back island” dune formation and the wind- and water-swept fine sediments of the marsh and tidal flats. Each part of the beach has a unique and delicate habitat for specialized flora and fauna – which include fish, invertebrates, birds, and many other species.

There is so much to see at our beach parks. Consider these questions when you visit the barrier island – we will have fun talking through the answers:

- Why is it called a barrier island? Is “barrier” a geographic name or a function? How might the role of barrier be more important to convey than the place of barrier?

- Where (what part of the island) is the wind and wave energy concentrated? If energy and grain-size are proportional, where would you find the coarsest sand grains (or larger) on a barrier island?

- If barrier islands formed with slowing rates of sea level rise, what is the greatest jeopardy of CO2 associated climate change?

- As a dynamic part of the coastal system, barrier islands move and change in a natural cycle. What effects, positive or negative, might human infrastructure and habitation have on the island?

- If the ocean rises to 20 ft. in a hurricane storm surge, does it hurt or help the barrier island?

Randy Bissell – Texas Master Naturalist & Professional Geoscientist

June 20, 2020