The Twelve Soil Orders

Soil Taxonomy is a soil classification system developed by the United States Department of Agriculture’s soil survey staff. This system is based on measurable and observable soil properties and was designed to facilitate detailed soil survey. Although it is not the only system for classifying soils, Soil Taxonomy is widely used worldwide and many of its features have been adopted into other systems.

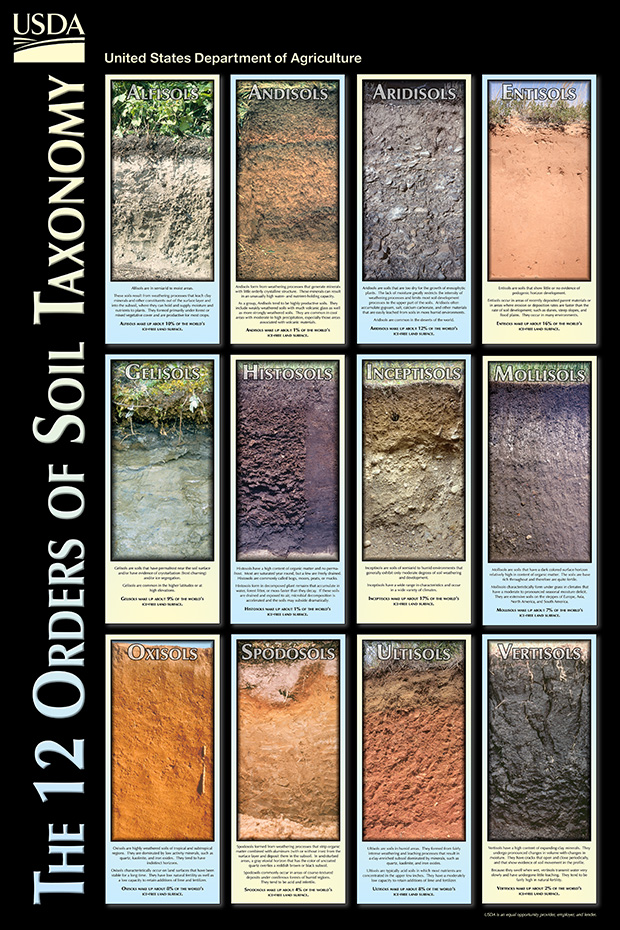

At the highest level of classification, Soil Taxonomy places soils into one of 12 categories known as “orders.” Each of these orders represents a grouping of soils with distinct characteristics and ecological significance.

The soil orders simplified

To identify, understand, and manage soils, soil scientists have developed a soil classification or taxonomy system. Like the classification systems for plants and animals, the soil classification system contains several levels of detail, from the most general to the most specific. The most general level of classification in the United States system is the soil order, of which there are 12 (see: https://www.soils.org/discover-soils/soil-basics/soil-types).

Each order is based on one or two dominant physical, chemical, or biological properties that differentiate it clearly from the other orders. Perhaps the easiest way to understand why certain properties were chosen over others is to consider how the soil (i.e., land) will be used. That is, the property that will most affect land use is given precedence over one that has a relatively small impact.

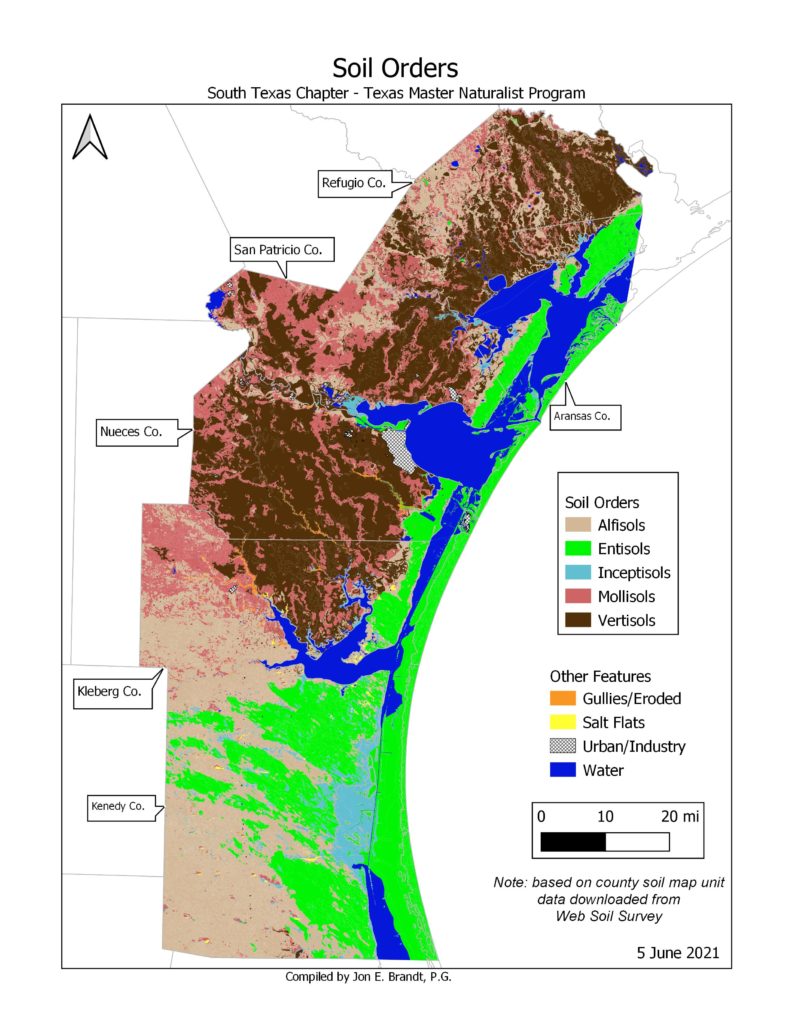

The 12 soil orders are presented below in the sequence in which they “key out” in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s dichotomous Soil Taxonomy system. Important: South Texas Soil Orders included in the map below are in BOLD FONT

Alfisols

Alfisols (from the soil science term Pedalfer – aluminum and iron) are similar to Ultisols but are less intensively weathered and less acidic. They tend to be more inherently fertile than Ultisols and are located in similar climatic regions, typically under forest vegetation. They are also more common than Ultisols, occupying about 10% of the glacier-free land surface.

Aridisols

Aridisols (from the Latin aridus – dry) are soils that occur in climates that are too dry for “mesophytic” plants—plants adapted to neither too wet nor too dry environments—to survive. The climate in which Aridisols occur also restricts soil weathering processes. Aridisols often contain accumulations of salt, gypsum, or carbonates, and are found in hot and cold deserts worldwide. They occupy about 12% of the Earth’s glacier-free land area, including some of the dry valleys of Antarctica.

Entisols

Entisols (from recent – new) are the last order in soil taxonomy and exhibit little to no soil development other than the presence of an identifiable topsoil horizon. These soils occur in areas of recently deposited sediments, often in places where deposition is faster than the rate of soil development. Some typical landforms where Entisols are located include: active flood plains, dunes, landslide areas, and behind retreating glaciers. They are common in all environments. Entisols make up the second largest group of soils after Inceptisols, occupying about 16% of the Earth’s surface.

Inceptisols

Inceptisols (from the Latin inceptum – beginning) exhibit a moderate degree of soil development, lacking significant clay accumulation in the subsoil. They occur over a wide range of parent materials and climatic conditions, and thus have a wide range of characteristics. They are extensive, occupying approximately 17% of the earth’s glacier-free surface.

Mollisols

Mollisols (from the Latin mollis – soft) are prairie or grassland soils that have a dark colored surface horizon, are highly fertile, and are rich in chemical “bases” such as calcium and magnesium. The dark surface horizon comes from the yearly addition of organic matter to the soil from the roots of prairie plants. Mollisols are often found in climates with pronounced dry seasons. They make up approximately 7% of the glacier-free land surface.

Vertisols

Vertisols (from the Latin verto – turn) are clay-rich soils that contain a type of “expansive” clay that shrinks and swells dramatically. These soils therefore shrink as they dry and swell when they become wet. When dry, vertisols form large cracks that may be more than one meter (three feet) deep and several centimeters, or inches, wide. The movement of these soils can crack building foundations and buckle roads. Vertisols are highly fertile due to their high clay content; however, water tends to pool on their surfaces when they become wet. Vertisols are located in areas where the underlying parent materials allow for the formation of expansive clay minerals. They occupy about 2% of the glacier-free land surface.

Gelisols

Gelisols (from the Latin gelare – to freeze) are soils that are permanently frozen (contain “permafrost”) or contain evidence of permafrost near the soil surface. Gelisols are found in the Arctic and Antarctic, as well as at extremely high elevations. Permafrost influences land use through its effect on the downward movement of water and freeze-thaw activity (cryoturbation) such as frost heaves. Permafrost can also restrict the rooting depth of plants. Gelisols make up about 9% of the world’s glacier-free land surface.

Histosols

Histosols (from the Greek histos – tissue) are dominantly composed of organic material in their upper portion. The Histosol order mainly contains soils commonly called bogs, moors, peat lands, muskegs, fens, or peats and mucks. These soils form when organic matter, such as leaves, mosses, or grasses, decomposes more slowly than it accumulates due to a decrease in microbial decay rates. This most often occurs in extremely wet areas or underwater; thus, most of these soils are saturated year-round. Histosols can be highly productive farmland when drained; however, drained Histosols can decompose rapidly and subside dramatically. They are also not stable for foundations or roadways, and may be highly acidic. Histosols make up about 1% of the world’s glacier-free land surface.

Spodosols

Spodosols (from the Greek spodos – wood ash) are among the most attractive soils. They often have a dark surface underlain by an ashy gray layer, which is subsequently underlain by a reddish, rusty, coffee-colored, or black subsoil horizon. These soils form as rainfall interacts with acidic vegetative litter, such as the needles of conifers, to form organic acids. These acids dissolve iron, aluminum, and organic matter in the topsoil and ashy gray (eluvial) horizons. The dissolved materials then move (illuviate) to the colorful subsoil horizons. Spodosols most often develop in coarsely textured soils (sands and loamy sands) under coniferous vegetation in humid regions of the world. They tend to be acidic, and have low fertility and low clay content. Spodosols occupy about 4% of the world’s glacier-free land surface.

Andisols

Andisols (from the Japanese ando – black soil) typically form from the weathering of volcanic materials such as ash, resulting in minerals in the soil with poor crystal structure. These minerals have an unusually high capacity to hold both nutrients and water, making these soils very productive and fertile. Andisols include weakly weathered soils with much volcanic glass, as well as more strongly weathered soils. They typically occur in areas with moderate to high rainfall and cool temperatures. They also tend to be highly erodible when on slopes. These soils make up about 1% of the glacier-free land surface.

Oxisols

Oxisols (from the French oxide – oxide) are soils of tropical and subtropical regions, which are dominated by iron oxides, quartz, and highly weathered clay minerals such as kaolinite. These soils are typically found on gently sloping land surfaces of great age that have been stable for a long time. For the most part, they are nearly featureless soils without clearly marked layers, or horizons. Because they are highly weathered, they have low natural fertility, but can be made productive through wise use of fertilizers and lime. Oxisols are found over about 8% of the glacier-free land surface.

Ultisols

Ultisols (from the Latin ultimus – last) are soils that have formed in humid areas and are intensely weathered. They typically contain a subsoil horizon that has an appreciable amount of translocated clay, and are relatively acidic. Most nutrients are held in the upper centimeters of Ultisol soils, and these soils are generally of low fertility although they can become productive with additions of fertilizer and lime. Ultisols make up about 8% of the glacier-free land surface.