Article and Photos by Karen Glenn, Blackland Prairie Master Naturalist; Submitted by Patricia Crain, Class of 2018

One thing I really love about the concept of rewilding is the opportunity to take things slow. It is a process of working with nature and looking at a habitat from the perspective of native flora and fauna. Farming and gardening are mostly based on a human perspective of land use. Permaculture practices were movements towards rewilding, and while building a permaculture is much better for the native habitat, the practices still focus on a human-needs perspective. While I add my own food plants here and there, true rewilding looks at things from the perspective of what is best for all the members of the habitat: soil microorganisms, plants and animals. With modern practices we have increasingly gone to war with the natural processes that have taken place on this land for tens of thousands of years.

A rewilding perspective realizes nature is much better at taking care of itself than we are, because we are not aware of all the pieces present on our land and how they all interact. There are many species we are not even aware of co-habiting with us. The hardest thing about rewilding is letting go of our human perspective enough to release control. Thinking as an observer and member of the local ecosystem, instead of the sole master of it.

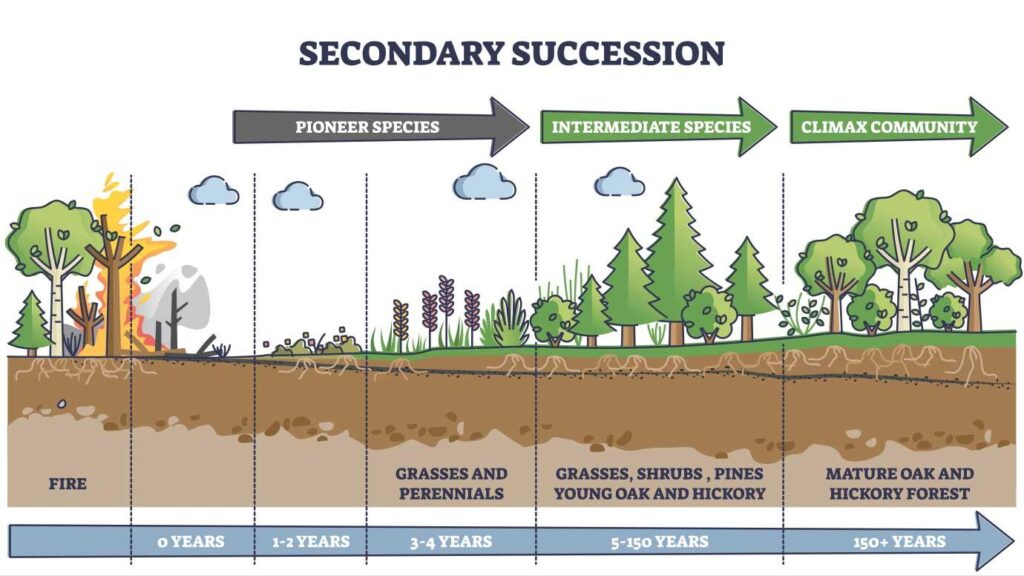

Once mowing and clearing stops in a habitat the native plants will attempt to reestablish themselves. Letting that happen – the new buzz word is nonmanagement – allows the habitat to go into its recovery mode. A well-kept lawn tries to stop this repair system in the natural habitat. This is why it is so difficult to keep weeds out of your lawn. They are relentless in their duties! My goal is to help keep my small piece of land in a mid-secondary succession stage. The first 3-4 years were spent observing the land and getting to know plants as they appeared. Annuals tend to show up first, followed by perennials. Once the perennials become established the habitat begins to settle into a more stable mixture of plants and animals. Now it is time to manage the woody growth to give the forbs the room and light they need to remain in place. The battle is much slower paced than trying to keep a weed-free lawn!

Weedy annual native plants will be the first to arrive within a disturbed space as pioneer plants. They usually produce a ton of seeds, and this is the constant struggle we find ourselves in: fighting weeds to keep the perfect lawn or garden. From the habitat perspective this space has been severely disturbed, and pioneer plants come in to cover the soil, repair the damage, and make way for the habitat to become established with native grasses, forbs, and trees. Once they do their job they are replaced within 3-5 years with perennial species, trees, and shrubs, which provide important food and shelter in the habitat. Within a few years the pioneer “weeds” will give way to longer-lived native forbs and grasses. This is why the first couple of years are the hardest. It requires patience, leaving the system alone to do its work.

As humans we tend to want everything to be in neat rows and perfect rectangular beds. Societal pressure dictates everything must be a controlled and uniform length. Square corners and straight lines look pleasant for human eyes. It shows human effort and control. Meanwhile, native plant communities, when left on their own, tend to be diverse and messy. Try to find a monoculture of grass or fruit trees growing in a perfectly straight line out in nature, without some kind of disturbance influencing where the seeds settle. Build a fence and soon a line of trees will form in a neat line.

It is easy to fall in love with diversity on the property. It isn’t so easy to fall in love with the messiness of some seasons, but everything deserves time to rest occasionally, and a native habitat is no different. There are a few bare spots here and there due to the lack of rain. Several species of ants are abundant on the property, and I have noticed antlion pit traps have been popping up in the sandy areas. A few adults have been spotted in the yard, but I never seem to have my camera when they do. It is much easier to take pictures of their larval homes! The larval stages of this insect require relatively undisturbed, bare ground to successfully reach adulthood, and it may take up to two years to fully develop into a winged adult. Most of their life span is spent in the larval stage eating ants and other small insects that fall into their traps. Antlion pit traps used to be everywhere when I was a kid, but I do not see them much anymore. Now that I know they are here I will make sure there is always a bit of bare ground for them to go through their 2-year pupating stage.

This guide is a good resource for learning about the insects in our area.

I never noticed adult antlions in the habitat, until I started looking for them. They resemble small, dull-colored damsel flies with club-shaped antennae. Antlions, damselflies, and dragonflies do an immense job of controlling pest species in the habitat. Their numbers automatically adjust to match the forage available, although their appearance sometimes lags behind their prey items by a season or two. It is tempting to reach for the pesticides, but waiting usually pays off with a permanent solution. All we have to do is get out of their way and not interfere with their work. The native plants and animals already have systems in place to restore balance and heal the land. When we learn to work with these systems, instead of against them, beautiful things begin to happen.

Read more about Karen Glenn’s Rewilding Sticker Hill Project