Copeland, Florida, 2011. Margaret Webb, a 90-year-old at the time, was walking by a canal near her home. It was a perfect day. The sky seemed like blue porcelain, and a gentle breeze brought with it a premonition of fall. As she labored along, the reflected sky ran like a vein of silver in the canal. Margaret loved everything about her walks: the birdsong, the lush surroundings, the water. What she didn’t see was a nearly 8-foot alligator bent like a stick half-immersed in the water. The gator lunged and grabbed her in a micro flash. The reptile tried to haul her back into the water, but Webb was tougher than she looked. Somehow, she managed to hold onto dry land long enough to catch the attention of a stranger who scared the gator away—like a dog from a butcher’s yard. Margaret survived. . .but lost part of her leg in the attack. Her days of enjoyable walks, gone forever.

Like a scene out of Jurassic Park, this tragedy illustrates in stark terms what it means to be an opportunistic feeder. The crocodilian order of reptiles contains some of the most fearsome apex predators on earth. Alligators and crocodiles are the only remaining vestal metaphors we have for living dinosaurs. They are not dinosaurs, but related; astonishingly they survived the extinction event of 65 million years ago.

The American alligator is a killing machine, quick and violent. Their menacing jaws are not made for chewing slowly—gators eat like dogs under the dinner table. While ungainly on land, gators are powerful swimmers. They use their sharp teeth to seize and hold prey, either swallowing it whole, shaking it apart into smaller, manageable pieces or pulling it under water to drown. If they have especially large prey, they bite their quarry, then spin on the long axis of their bodies to tear off easily swallowed pieces. Unwary children and pets walking near the water’s edge make easy targets. Adults are not often attacked but, as we’ve seen, it can happen.

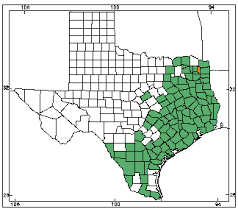

American alligators live primarily in the southeastern United States, mostly Florida and Louisiana. But they also inhabit the Atlantic Coast of North America and the eastern third of the Gulf Coast of Texas. They hang out in swamps, rivers, bayous, and marshes. Alligators prefer fresh water, but can tolerate brackish water for short periods, so you can’t trust regional saltwater marshes. While Texas is not commonly considered gator country, they inhabit 120 counties from the Sabine River of east Texas, across the coastal marshes of the Gulf of Mexico, and on west to the Rio Grande. Formerly an endangered species, the American alligator is now a protected game animal in Texas. You must have special permits to hunt, raise or keep alligators.

There are only two species of alligators—the Chinese and the American alligator. Their name comes from a corruption of the Spanish word for lizard (el lagarto). People often get crocodiles and alligators confused. It’s easy. With exception of the endangered American crocodile in southern Florida, if it’s in the U.S., it’s an American alligator. Crocs live in tropical/sub-tropical climates and have elongated snouts—alligator snouts are blunter and more rounded. Alligators can grow more than 13 feet long and weigh in at 1,000 pounds. You can also tell an alligator from a crocodile by the teeth. The large, fourth tooth in the lower jaw of an alligator fits into a socket in the upper jaw and is not visible when the mouth is closed. In crocodiles, these teeth are exposed. Alligators have somewhere between 74 and 80 teeth in their mouth at a time. As an alligator’s teeth wear down or fall out (a fairly regular occurrence), new ones come in. A gator can go through as many as 3,000 teeth in a lifetime (60 + years).

Alligator evolution has successfully moved through 150 million years. They have 5 toes on their front feet but 4 webbed toes on each rear foot. Given a long powerful tail, we’re talking about a wicked fast swimmer. Michael Phelps wouldn’t stand a chance! Not known for great eyesight, gators have good hearing and are especially sensitive to vibrations in the water. It’s no wonder then, they spend a lot of time floating or cruising with only their eyes and nostrils showing. Being cold-blooded, they eat surprisingly little. A 100-pound dog eats more in a year than an 800-pound alligator. On hot summer days they can sometimes be seen basking with their mouths open. This is a cooling mechanism, essentially equivalent to a dog panting.

Gators do have their quirks. For example, they have an incredibly strong homing instinct. Biologists have discovered problem gators are difficult to relocate. Situations show some can return to home waters after being moved over 100 miles. This amazing ability to navigate has caused the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources to declare alligator relocation illegal in the state. Also, even though gators don’t hibernate, they do slow down (bromate) when the weather turns cold. With their powerful tails, they form “gator holes” to provide protection from the cold. In hot summers, alligators dig these holes into the mud, which fills with water to help regulate body temperature. Some holes can be 65 feet long and make great homes for other animal squatters afterwards.

Nighttime is when alligators hunt and are on the prowl. Texas alligators are mostly inactive from mid-October until early March when they emerge from brumation. March through May is the peak time for breeding and nesting. Sexual maturity is reached anywhere from 10-12 years of age. Know that alligators are one of only a few reptiles that actively care for their young. You don’t ever want to come between a mother and her brood.

As the evening turns its last shade the moon slinks out from under a cloud and sprouts a tail of light across the lake—there’s love in the air! Alligator courtship is a very noisy and physical process. Amorous males “bellow” and make a variety of other vocalizations to proposition females (and to warn other males). They also leave scent signals to let everyone know “it’s that time of year again.” Then there’s the male head-slapping against the water’s surface and different forms of body posturing, all of which are designed to showcase superior masculinity. Next—after looking into each other’s eyes, closing a circuit—comes snout and back rubbing as our romantic male rounds second base, headed for home. At the peak of the seduction comes bubble blowing. Ah yes, bubble blowing. What female can resist? This is the ultimate expression of alligator sensuality—and it drives her out of her mind!

Usually, by June pairs have mated and females have built mound nests out of marsh reeds or other vegetation. Females lay from 20 to 60 eggs which incubate for about 65 days. The rotting vegetation covering the nest actually helps heat and incubate the eggs, and, it turns out, this temperature gradient ultimately determines the sex of the hatchlings (temps of 87.8 F or below produce females, males require a range from 87.9 F to 90.4 F, while higher temps, once again, produce mostly females). When the time is right, the mother alligator digs into the nest mound, opens any eggs that have not hatched and carries the hatchlings down to the water, where she sometimes aggressively defends her babies for more than a year.

The American alligator is a rare success story of a once endangered animal not only saved from extinction but now thriving because of those protections. We don’t know for sure, but the Texas alligator population is believed to run somewhere between 500,000 to a million or more. Alligators have been found in at least 31 lakes in the state and TPWD is good about placing warning signs about alligators in affected state parks. There have been only two fatal alligator attacks in Texas in the last 200 years. Living safely with the American alligator requires vigilance, observing warnings and common sense. Keep your eyes open around water and shorelines, protect your pets and small children, don’t feed or interact with the animals, and don’t swim at dusk or at night.

Most cringe at the sight of alligators lounging with feigned boredom along a bank. As eyes connect, there is an instant of silent primal communication—we know that in a contest we would be prey. For this reason, most people consider them monsters, but monster is a relative term; to a canary a cat is a monster. In a rare moment of insight, we have acted on the realization that we are the monsters. We have a history of killing for parking lots and high rises, feathers for our hats, furs for our shoulders, and handbags to match. Were it not for legislative protections, humankind would almost certainly have hunted alligators to extinction. The question now. . .can we also save ourselves from extinction?

By Larry Gfeller