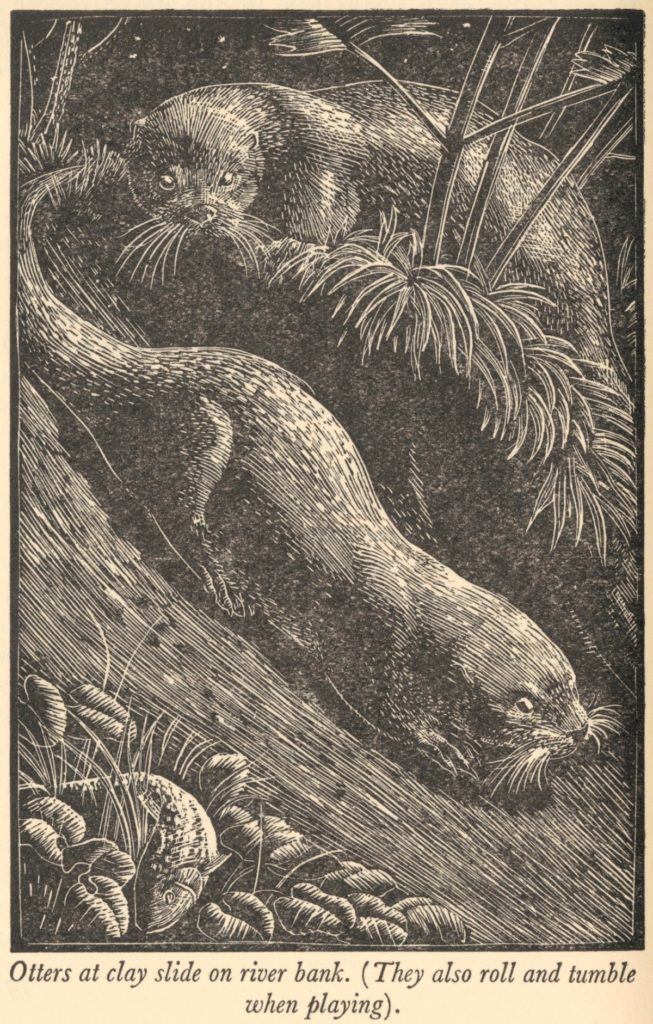

The air carries a muddy edge, the smell of river water in mid-winter. It’s time to play. There’s a flutter in my stomach, like a snagged plastic bag flapping in the wind, those first moments when I think about what I’m about to do. Peering through the desiccated bankside weeds, my buddy behind me feels it too—we can almost hear each other’s heartbeats. The wet slippery bank stretches before us toward water cold enough to stop a heart. Being on land is a vulnerability for us both; there’s not a more dangerous time. So, I push off, belly on the slick shiny mud, face first, front legs folded back, catapulting like a bobsled down a chute to the water below. My buddy launches a split second after me. It’s an exhilarating, electric feeling as the bottom drops out of my stomach. Holy _ _ _ _, what a ride!! Two splashes followed by a pure surge of pleasure, a flash flood of joy! This is how you spend your days on sunny January afternoons—when you’re a fun-loving otter!

Here’s my gig. . .I’m supposed to talk about what it takes to be a successful otter (as opposed to what, I guess, a squirrel?). Well, otter requirements are simple: clean water and plenty of fish! With those two things, the right body, and a little practice you too can be at home in any river, tributary, or stream. Now about that body, you’re gonna need a few specialized features like webbed feet, thick waterproof fur, flat broad tail, eyes, ears, and nostrils on top of your head (all closed off or functional under water), and strong hind legs. It also helps to have long, sensitive whiskers to find those fish in the rocks and shoals. In the water I can dash about, turn on a dime, and move like the wind. I can dive over 30 feet down and hold my breath for 4 minutes or more. And I love to play with my friends: tag, slippery slides, tail chasing—it’s all good. I’m lightning fast in the water! On the ground, not so much (but I can still boogey when I need to).

I’ve got a slew of relatives, so folks often confuse me with some of my distant cousins. For example, I don’t float on my back in the ocean and crack open oysters on my chest—that’s my bigger North American kin, the sea otter. Hell, I don’t even know how to float; don’t like saltwater, never tasted oysters. There are, I believe, 12 other branches in my family tree scattered around the world. They live in foreign places like Europe, Asia, Africa, South and Central America and have slightly different names. Me? I live in the Piney Woods of eastern Texas, and I’m a bonified North American River Otter.

My kind live in much of the eastern United States and throughout Canada. Those of us who reside in Texas are expanding our boundaries. You see, our great-great grandparents were nearly hunted to extinction for their soft brown fur, and many of them ended up as hats or mittens. Subsequent generations faced the building of farms, fences, highways and eventually high-rises—making it hard to find a place to raise a family. Today Texas real estate has become so dear and our population so desperate that we’re showing up in places we would’ve never considered before. We’ve moved into the Buffalo Bayou of downtown Houston, waterways in the Dallas-Fort Worth region, been sighted in Wichita Falls, Gonzales, and lakes Lavon and Grapevine. Some of us are migrating further west into small suburban creeks and backwaters. Don’t be surprised if you find us borrowing your stock tanks, ranch ponds, or even golf course water features.

Here’s the deal, if you want to make it as a river otter you need to be very social and friendly. We’re a tight group and nobody likes a grump. Even though the solitary life is typical, you will, from time to time, need to join in other otter groups. There’s mothers with their pups, occasional fraternities of guys living and hunting together, or just partying with extemporaneous playmates. Otters just like to have fun. There’s some unwritten rules of etiquette you must learn for proper communication and socializing. We communicate with growls, whistles, yelps—even touch—and by marking our territory. When going potty, one of the best ways I know to get thrown out of a group is to ignore the practice of community latrines. It’s all about “spraint.” Spraint is what results from our aquatic diet; crawfish exoskeletons, fish scales and animal bones that cannot be properly digested. Yuck! No one wants that stuff where you live and play. So, if you want to be part of a group, make sure and use the public latrine!

Another piece of advice: always locate your home near the water’s edge—it’s where the action is. Fallen logs, tree roots and rock piles are ideal. Under water access is a plus. Discriminating otters set up mancaves and she-sheds in old muskrat dens or beaver lodges. Sometimes you first have to persuade the current inhabitants to leave (leaving a little spraint around on the inside helps them make the right decision). The Texas Gulf Coast region also provides plenty of food, but you have to settle for empty hollows of grass and mud in marshes, bayous or backwater inlets. Not the best neighborhood, but hey—it beats homelessness by a long shot.

When it comes to eating well, remember you’re a predator. That means seizing opportunities. If you’re willing to take a chance on land, you can score some surprising meals. A nest full of bird eggs or baby rabbits is a special find—paarrr-tteeee! Most of your meals, however, will be taken in the water. If you see mamma duck, for example, swimming with her ducklings trailing behind: silently, silently. . . only your nostrils, eyes, and ears exposed. . .you gotta believe she’ll never miss that last one! Ala carte treats include fresh water mussels, crawdads, frogs, crabs, snakes and small turtles. The main entree, though, is slow moving fish. Perch and small bass may be enjoyed in the water but you may have to wrestle that catfish up on the bank to finish the meal. Man, that’s good eatin’! When food is scarce, you’ll have to choke down your vegetables in the form of selected aquatic plants. Even insects in a pinch. Point is, we otters have a very high metabolism so we’ve gotta constantly stuff our pie hole.

No tutorial would be complete without mentioning the birds and bees. Otter sex is impersonal and necessary, like a cloudburst. Naturalists call it “spawning,” but to be clear, we’re talking about frenzied, bodice-ripping sex. It takes about 2-3 years to get all the equipment you need to make babies. Finding a mate usually happens in late winter or early spring. It’s not as easy as you think, especially if the ratio of sexes is out of whack in your area. That’s okay, it’s why we’ve got legs. Successful otters can travel almost 20 miles over land with no problem—not our preference, but it works—and we all know persistence pays off. Ladies, you’ve got to be wary of those smooth talking, show-off males who try to impress you with their acrobatics. What you need to be looking for is great genes. Guys are only in it for the sex, so pick carefully and enjoy yourself—because afterwards you’ll never see the bum again!

Mothers can expect to deliver anywhere from 2-4 pups in March or April, and they’re very needy at first (blind, toothless, and completely helpless). The pups are sheltered in the den as a family for 7-8 months—locked up tighter than virgins in a boarding school. After about 2 months though, the little ones need to learn to swim. With a gentle touch, mom takes them one at a time by the scruff of the neck and swims with them until they get the hang of it. Soon, however, their playful nature helps them learn to swim and hunt. You can expect to live 8-9 years if you keep a sharp eye out for coyotes, bobcats, big raptors, or alligators.

Everyone should want to be a North American river otter. I can vouch that few creatures on earth enjoy their lives more; who do you know whose purpose is to spend a lifetime fishing and playing? We are also good stewards of our ecosystem. By controlling the numbers of fish, crustaceans and other prey, we help maintain a healthy food web. And there’s good news for humanity too. If you see us in your area, you can bet the habitat is clean and healthy. So, give us a hand and conserve water and reduce pollution. I figure you owe that much to the memories of my great-great grandparents!

By Larry Gfeller